At a glance

Why "nitpickings"?

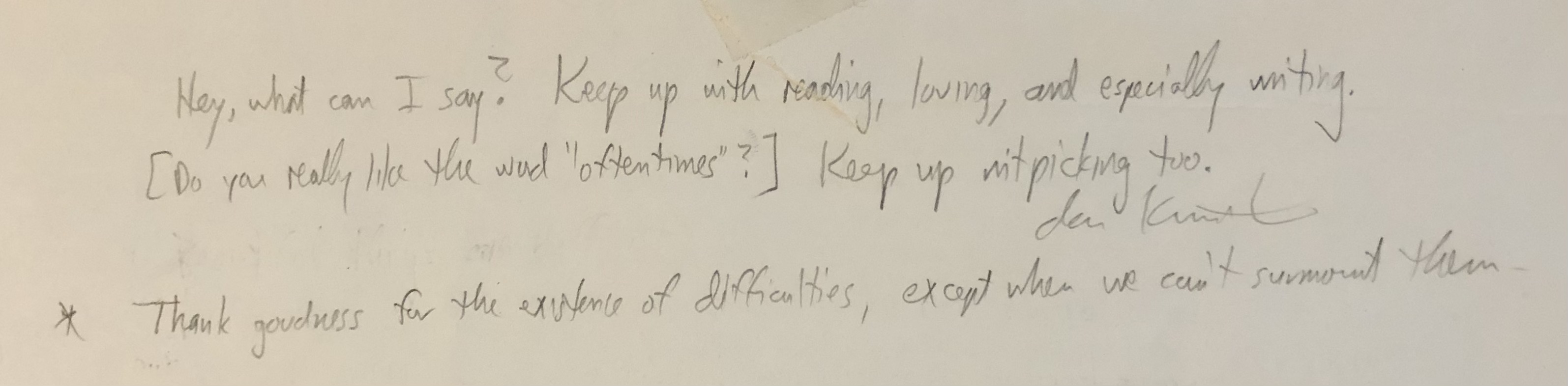

Some years ago I asked Donald Knuth, known by some as the Yoda of silicon valley, for any advice he might have in my pursuit of mathematics. His response was heartwarming, especially given the context.[*]:

In type:

Hey, what can I say? Keep up with reading, loving, and especially writing. [Do you really like the word "oftentimes"?] Keep up nitpicking too.

don knuth* Thank goodness for the existence of difficulties, except when we can't surmount them.

I appreciated his advice throughout undergrad as well as my first years of teaching mathematics. And I now appreciate his advice all the more as a software engineer. Why? Because it encourages an often undervalued practice: nitpicking.

Nitpicking on its own usually has a pejorative connotation, as its Wiki entry makes clear:

Nitpicking is a term, first attested in 1956, that describes the action of giving too much attention to unimportant detail. A person who nitpicks is termed as a nitpicker. [...] As nitpicking inherently requires fastidious attention to detail, the term has become appropriated to describe the practice of meticulously searching for minor, even trivial errors in detail.

But isn't it such attention to detail that leads to myriad innovations in the arts and sciences (e.g., software development and mathematics)? It is perhaps more useful, especially in technical fields, to think of "nitpicking" as a form of curiosity in service of improving whatever nit is being picked. Said another way, the kind of ideal nitpicker I have in mind is one who asks seemingly simple questions but seeks potentially profound answers. The nitpicker's favorite question is simple: Why?

The daybook

Suppse you've been fortunate enough to discover that one of your seemingly simple questions was not, in fact, so simple after all, and the process of trying to answer your question has led you to identify some profound truth. What should you do with your newfound truth? You should record it! Where? In a daybook! What's a daybook?

The idea of an "engineering daybook" is explored more in [11], but the relevant excerpt is reproduced below for the sake of clarity:

Dave once worked for a small computer manufacturer, which meant working alongside electronic and sometimes mechanical engineers.

Many of them walked around with a paper notebook, normally with a pen stuffed down the spine. Every now and then when we were talking, they'd pop the notebook open and scribble something.

Eventually Dave asked the obvious question. It turned out that they'd been trained to keep an engineering daybook, a kind of journal in which they recorded what they did, things they'd learned, sketches of ideas, readings from meters: basically anything to do with their work. When the notebook became full, they'd write the date range on the spine, then stick it on the shelf next to previous daybooks. There may have been a gentle competition going on for whose set of books took the most shelf space.

We use daybooks to take notes in meetings, to jot down what we're working on, to note variable values when debugging, to leave reminders where we put things, to record wild ideas, and sometimes just to doodle.

The daybook has three main benefits:

- It is more reliable than memory. People might ask "What was the name of that company you called last week about the power supply problem?" and you can flip back a page or so and give them the name and number.

- It gives you a place to store ideas that aren't immediately relevant to the task at hand. That way you can continue to concentrate on what you are doing, knowing that the great idea won't be forgotten.

- It acts as a kind of rubber duck. When you stop to write something down, your brain may switch gears, almost as if talking to someone a great chance to reflect. You may start to make a note and then suddenly realize that what you'd just done, the topic of the note, is just plain wrong.

There's an added benefit, too. Every now and then you can look back at what you were doing oh-so-many-years-ago and think about the people, the projects, and the awful clothes and hairstyles.

So, try keeping an engineering daybook. Use paper, not a file or a wiki: there's something special about the act of writing compared to typing. Give it a month, and see if you're getting any benefits.

If nothing else, it'll make writing your memoir easier when you're rich and famous.

This site comprises my own personal "daybook" of sorts, albeit not the pen-and-paper type described in the excerpt above. How so? Because on this site you'll find many of the things I've learned, sketches of ideas, and basically anything to do with my work. Content is largely presented in one of three flavors:

- Core content: Posts meant to be maintained over time given their perceived significance (e.g., window functions in SQL)

- Nit Wits: Essentially a blog with self-contained posts (e.g., introduction to monotonic stacks and queues)

- Daily nitpickings: Loosely organized accounts of different things I've learned or found notable on different days — these entries more closely align with the daybook entries discussed in the excerpt above. I should note I also keep separate pen-and-paper journals in the flavor of [21] and [22] because I also agree that there is something special about the act of writing compared to typing.

Some notable entries are provided below for ease of reference:

Core Content

Data Structures Overview

Check out time and space complexity overviews for various data structures and array sorting algorithms.

Window Functions (SQL)

Feynman Technique

Definitions, theorems, and results

A cumulative list of definitions, theorems, and results can be quite useful, especially when you are in need of a dust-up or review.

Nit Wits

Comments with Giscus

This blog post details how to enable comment sections on doc pages and blog entries on sites powered by Docusaurus (like this one) using giscus.

Light/Dark Modes with Material UI and Docusaurus

This blog post details how to synchronize the default light and dark mode palettes used in Material UI with the light or dark mode being used on a Docusaurus site.

External Resources

Docusaurus Input-Output Examples

Collection of input-output examples for use with sites powered by Docusaurus.

KaTeX Reference

Basically the KaTeX documentation site (but everything is ensured to work with Docusaurus).

MySQL Reference

Easy-to-use references to many MySQL functions (e.g., string functions, date functions, etc.).

Postgres Reference

Easy-to-use references to many Postgres functions (e.g., string functions, date functions, etc.).

PG Exercises Reference

Comprehensive reference for the popular online Postgres Exercises tutorial.

Site inspiration and delivery from preliminary terrors

Have you ever refrained from asking a question because you were terrified of possibily looking like an idiot? If so, then maybe you can identify with this meme (I know I can):

If you have experience with seeking technical help on the internet (e.g., Stack Overflow for programming, Math Stack Exchange for math, etc.), then you are probably familiar with the fact that these communities are often less than welcoming. More like openly hostile. A common trope is for users to post answers that serve little more than to stroke their own ego while leaving the person who asked the question more confused (and frustrated) than ever. Carl Linderholm hit on this exact theme as far back as 1971 in the introduction to his satirical book Mathematics Made Difficult [8]:

There is no doubt that an absolute ignoramus (not a mere qualified ignoramus, like the author) may become slightly confused on reading this book. Is this bad? On the contrary, it is highly desirable. Mathematicians always strive to confuse their audiences; where there is no confusion there is no prestige.

Even further back, in 1910, Sylvanus Thompson remarked on the tendency of authors in mathematics to make matters unnecessarily difficult in an attempt to appear clever. He had the following to say in the brief prologue to his book Calculus Made Easy [26]:

Considering how many fools can calculate, it is surprising that it should be thought either a difficult or a tedious task for any other fool to learn how to master the same tricks.

Some calculus-tricks are quite easy. Some are enormously difficult. The fools who write the text-books of advanced mathematics — and they are mostly clever fools — seldom take the trouble to show you how easy the easy calculations are. On the contrary, they seem to desire to impress you with their tremendous cleverness by going about it in the most difficult way.

Being myself a remarkably stupid fellow, I have had to unteach myself the difficulties, and now beg to present to my fellow fools the parts that are not hard. Master these thoroughly, and the rest will follow. What one fool can do, another can.

Thompson makes good on his promise in the first chapter of his book, which is scarcely a page and titled To Deliver You from the Preliminary Terrors. Thompson's words are like a breath of fresh air (and effective reminder) for anyone who has ever taken Calculus:

The preliminary terror, which chokes off most high school students from even attempting to learn how to calculate, can be abolished once for all by simply stating what is the meaning — in common-sense terms — of the two principal symbols that are used in calculating.

These dreadful symbols are:

which merely means "a little bit of".

Thus means a little bit of ; or means a little bit of . Ordinary mathematicians think it more polite to say "an element of", instead of "a little bit of". Just as you please. But you will find that these little bits (or elements) may be considered to be infinitely small.

which is merely a long , and may be called (if you like) "the sum of".

Thus means the sum of all the little bits of ; or means the sum of all the little bits of . Ordinary mathematicians call this symbol "the integral of". Now any fool can see that if is considered as made up of a lot of little bits, each of which is called , if you add them all up together you get the sum of all the 's (which is the same thing as the whole of ). The word "integral" simply means "the whole". If you think of the duration of time for one hour, you may (if you like) think of it as cut up into little bits called seconds. The whole of the little bits added up together make one hour.

When you see an expression that begins with this terrifying symbol, you will henceforth know that it is put there merely to give you instructions that you are now to perform the operation (if you can) of totalling up all the little bits that are indicated by the symbols that follow.

That's all.

What's the purpose of including all of these different excerpts on this site? Because I want this site to be a sort of "Everyman" for people learning how to code. Check the ego at the door. Unfettered curiosity is the goal.

Specific admonitions

Content on this site may be highlighted in various ways depending on context. Specifically, an admonition may be used to alert the reader to content of a distinctive type:

This is a DWF alert. It's my way of making a statement within my own content. These alerts are essentially me talking to myself as if the reader is also present.

This is a key idea alert. I'm generally a fan of TLDR ("too long, didn't read"), but sometimes the goal isn't just to summarize something but to really highlight the key idea (e.g., algorithm idea, data structure purpose, etc.).

This is a performance alert. Such alerts will generally be used in the context of data structures and algorithms content and may point to how to execute some task in a performant manner.

This is an extension alert. Such alerts are likely to occur in problem-solving contexts in the guise of a "follow-up" or something similar.

This is a study alert. Sometimes the best way to learn something is to study original sources, white papers, etc. Links highlighted in these alerts will usually be something more than just a link to refer to but something to actually spend some time with.

This is a toolbox disclaimer alert. This generally means whatever you're looking at is actively under construction and is likely to be changed imminently or in the near future (e.g., unpolished core content, incomplete blog posts, etc.).

General admonitions

The admonitions above are unique to this site. More general admonitions are defined in a similar vein to infima alerts:

This is a danger alert. Something has either gone wrong or has a high likelihood of going wrong if this alert is not heeded.

This is a caution or warning alert. Ignore at your own risk!

This is an info alert. Helpful information is being provided that is not critical to the topic at hand but should probably be read regardless.

This is a success or tip alert. Something good or helpful is being discussed!

This is a secondary note alert. Ancillary information is being provided.